"How much longer, my God. How much longer?

Cuban officials add insult to injury, saying those protesting the massive power outage are "vandals," "drunks," "indecent," and "sellouts."

Desperate first-person accounts have been flowing out of Cuba this week as citizens struggled to recover from Friday’s national power grid collapse and Hurricane Oscar.

Officials said power was restored to the national grid as of Tuesday afternoon. But by Tuesday night all territories were experiencing blackouts and the government again suspended all non-vital businesses and shut down schools across the country, this time until Sunday 27 October.. Citizens have been notified of rolling, scheduled blackouts. Officials said the scheduled power outages would help avoid another nation-wide collapse of the system.

On Wednesday 22 October, the Electric Union reported an energy deficit of 1,024 megawatts, roughly a third of the national demand.

Regime officials explained the electrical grid collapse by saying, essentially, that it collapsed because the system had failed. As always, they pointed to the US’s partial and porous embargo—my describers—as the cause of the crisis, although the regime uses the term “blockade” rather than embargo.

The eastern part of the island was hit hard Sunday when Hurricane Oscar brought heavy rains, winds, flooding, and mud and rock slides. Many families lost everything they had, and those who didn’t will struggle for years to recover from ruined appliances to destroyed crops.

At least six Cubans lost their lives as a result of the storm. But with some communities still cut off from the rest of the country, many fear the death toll will increase.

Across the country power outages, food shortages, and lack of clean water are making already difficult living conditions unbearable. On a US-based rights group’s hot line, people have described trying to care for bed-bound relatives without the ability to wash them or offer them cold drinking water. One young mother lamented not being able to wash her toddler or offer him clean clothes. “How much longer,” she moaned in her message.

Scattered protests were reported in different locations since the crisis began on Friday. Authorities played down the number and nature of the protests, saying there were only a few incidents involving “vandals,” “drunks,” and “indecent” people.

The regime is claiming that at least intermittent power has been restored in many areas, including most of Havana. But even within Havana there are barrios whose power had still not been restored on Tuesday. In one poor Central Havana neighborhood, residents took to the streets to protest by banging pots and pans and shouting luz (light).

The Spanish word for a cooking pot is cacerola, and these cazerolazos, as the pot-banging protests are called, have led officials to issue fierce warnings that any “vandalism “and “drunkenness”—terms the regime uses to describe protests—will be harshly punished. (Link below is of a cacerolazo in front of provincial headquarters in Villa Clara on Sunday)

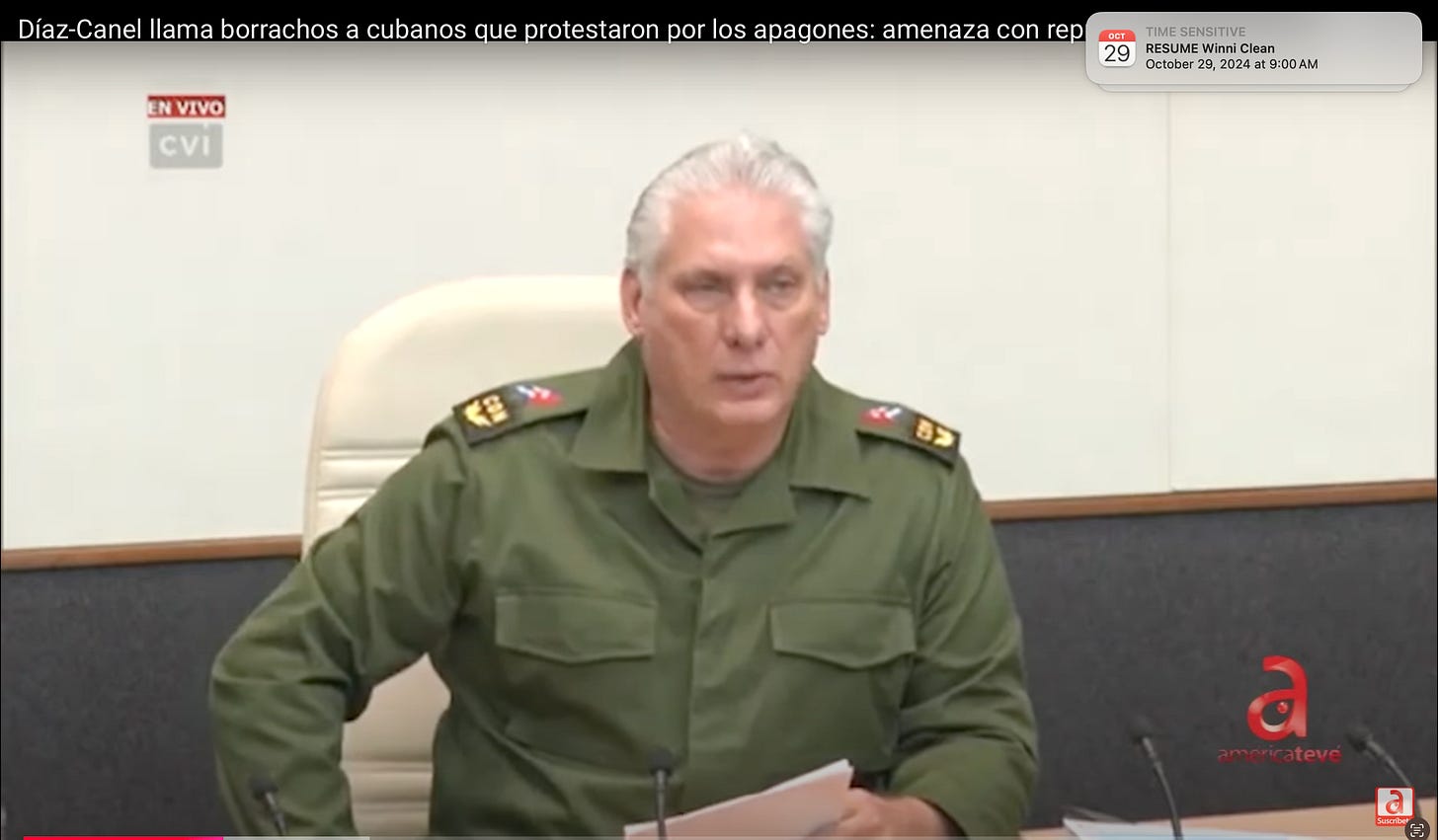

On Sunday, Díaz-Canel, in full military uniform rather than his customary civilian clothes, struck an authoritative, aggressive, and militant tone in a televised address to the nation. Echoing earlier statements by officials, he threatened protestors with extreme consequences. Bristling with defiance, he asserted that the regime “never had and never would permit the citizenry’s tranquility to be disturbed.”

Apparently, depriving Cubans of water and electricity for days on end, brutally punishing those who try to hold their government responsible for their hardship, and releasing attack dogs in barrios to quell unrest are not disturbing to Mr. Díaz-Canel.

Images and posts on across social media show or describe violent arrests in different locations where protests broke out. One activist I am in touch with posted a screen shot of messages from residents in one neighborhood that described beatings, “half the town being arrested,” and people being bitten by police attack dogs.

A report by Diario de Cuba features a clip in which a woman who’d been protesting in the street shouts “Abajo Díaz-Canel” and “Patria y Vida (anti-regime slogan), water, food” as several policemen haul her through the street and shove her into a patrol car. The man filming the scene, in Santiago de Cuba, says, “Look at this, people, they’re starving us, they’re taking everything from us, and look what they’re doing to her. Look at the abuse. Look at it.”

No one following Cuba news, and certainly not Cubans themselves, could have been surprised by the system-wide failure of the nation’s electrical grid. Cuban news regularly includes the megawatt energy deficit of the day, the latest power plants that are going offline due to repairs, and the hours and locations of rolling blackouts. The country’s thermoelectric plants are woefully outdated. Foreign experts monitoring Cuba’s system have long predicted the calamity that is now unfolding.

Cuba’s tourism sector—run by the military’s offshore conglomerate and heavily favored by the regime in terms of resources and investment—hasn’t returned to pre-pandemic levels and will likely be hit hard by the national grid’s collapse. 14ymedio spoke with seven owners of casas particulares (private home rentals) who said they’d received cancellations and worried more were on the way. The would-be visitors had read or watched news of the crisis and decided to change their plans.

Officials have told citizens to expect power outages to continue.

With the ailing system’s total collapse, the economy showing no sign of recovery, and the labor shortage due to the mass exodus—no one expects much from their light switches, or their sinks, or their fans.

In the words of that tired Cuban mother: Hasta cuando, Dios mío? Hasta cuando?

“How much longer, my God? How much longer?”