Famous Cuban activist on 5th day of hunger strike

Prison officials denied family's requests for proof of life. Worry mounts in activist community.

Sources: Diario de Cuba, 14ymedio, Cubanet.

19-25 June 2025

Hola y welcome back to CubaCurious.

Cuban musician Maykel Castillo Pérez should not be in hellish prison fearing for his life. His friends and family shouldn’t be agonizing about the 42-year-old political prisoner’s whereabouts, health, the physical and psychological abuses his guards mete out. Amnesty International, PEN Artists at Risk, members of the European Parliament, the U.S. State Department, and other institutions shouldn’t need to keep pleading for his safety and immediate release.

But they are, and they must. This week, again, Cuban authorities refused to answer questions about the high-profile political prisoner, an Amnesty International prisoner of conscience. Maykel Osorbo, his artistic name, declared himself plantado last week and began a hunger and thirst strike. The term means “planted,” as in firmly planted against his jailers, and Cuban political prisoners employ it only as a last resort. Many plantados have died or suffered irreversible organ damage over the last six decades of single-party rule.

The award-winning artist’s overseas supporters went into action when they heard the news. They know Maykel doesn’t bend to tyranny. He is committed to nonviolent human rights activism and democratic change for Cuba, but he is defiant by nature. He once sewed shut his mouth to show the world what life is like under a dictatorship.

Now he is standing firm again, plantado, to protest the latest threat he faces. Authorities said they’d be transferring him to an even more distant prison than Kilo 5 y Medio, the maximum-security prison he is in now. His family and friends currently travel 100 miles when they are permitted visits. The more distant prison is roughly 400 miles away. With the severe economic crisis, shortages of gasoline, and nonexistent public transportation, getting to the proposed prison would add a new insult to the distraught family.

At first Maykel’s relatives were met with total silence from prison authorities. But after a wave of social media criticism, officials finally contacted his father. Maykel isn’t on hunger strike, they said. Yes, he’s in solitary confinement—again—but no hunger strike here. He's being punished, they said, for “bad behavior.”

The next day, Maykel’s relatives traveled many hours to the prison seeking proof of life, in the form of a visit, or at least a phone call, so they could hear his voice. Many days had passed without word from him. Officials had denied call privileges as part of his punishment. The family’s assurance could only come from direct communication with Maykel.

The family waited many hours before officials met with them. Maykel had ended his hunger strike, they said. But officials had denied that he was on a hunger strike just the day before.

That’s right. The authorities were “reassuring” Maykel’s exhausted relatives that he’d ended the hunger strike that they had denied was happening the day before. Doble discurso, double-speak, thrives in an Orwellian state.

How did Maykel, a peace-loving, award-winning, human rights activist, land in this mess? Art.

The rapper coauthored the hit rap “Patria y Vida” and appeared draped in the Cuban flag in the music video. Patria y Vida (Homeland and Life) is an inversion of the revolutionary slogan Patria o Muerte (Homeland or Death).

The song won the Latin Grammy Song of the Year in 2021 and Best Urban Song. Maykel couldn’t collect the award that November. He was in a horrendous prison cell, awaiting trial for the supposed crime of, among others, “desecrating national symbols and martyrs.” He remained in prison for a year before a trial was held. He was sentenced to nine years’ imprisonment.

Cubans quickly adopted the song as a protest anthem when it was released in February 2021. And the regime just as quickly threatened, detained, or arrested anyone who played it or displayed the words.

“Patria y Vida” was, plainly and beautifully, a cry for freedom. Cubans protested the dictatorship by writing it on walls, sidewalks, their stomachs (easily covered up). They shouted it as they were arrested during protests. I heard it again this week in a recording of a protest about power outages.

Government approved pro-revolutionary groups organized the usual Rapid Response Brigades, which mount public humiliations known as “acts of repudiation,” to keep Cubans in check. The brigades rallied outside homes where the song had played, or activists lived. The brigade shouted insults, blasted patriotic songs, and sometimes assaulted activists and their families in the process.

In one case brigade members climbed over the fence of an activist family who had painted Patria y Vida on the wall of their home. The family, which including several young children and an elderly woman, hid inside as the brigade scaled the fence and spray painted over the slogan along with their door and windows.

The family filmed the assault from inside their home. You could hear them worrying—the kids were crying—about their dog, who was lying motionless outside their door. Later, after the fence-climbers retreated and the mob left, the family revived the dog. They believed he’d been drugged to allow the mob easy access to the home. I hope that dog lived and offered solace to the children who cried throughout the incident.

I’ve thought of those children a few times since I read the story in the spring of 2021. What would a child take away from such a scene, where a group of neighbors and strangers (the brigades run better when people from outside the barrio are in the mix) vandalize your home and shame your family? What would a child learn about their world when they realized their teachers were in the mob, too, yelling insults at them?

Children, I’ve found, know injustice even before they know how to read or write. They have an instinct for it. Maybe not the words, but they know it just the same.

Maybe that gut reaction, the need to stand against injustice, is in our DNA for a reason. Maybe that visceral response to profound unfairness shaped—saved?— our species.

I think the instinct to call injustice by name, point it out, and stand against it, exists to protect what Jose Marti described as “the essence” of life. Libertad.

Hasta la semana que viene,

Ana

NOTE: On Wednesday, June 25th, Anamely Ramos González, who serves as the artist’s spokesperson in the U.S., confirmed that Maykel is on the 5th day of his hunger strike. It is unclear if it is also a thirst strike. The information came through “fellow prisoners in solidarity with Maykel.” Maykel’s supporters have not succeeded in speaking with him directly. Publicity and pressure from the international community is crucial in ensuring Maykel’s safety. You can help by “liking” Anamely’s posts about his case. Here’s a link to a recent one, a video interview from 25 June. Posting comments in support of Maykel, using #freemaykelosorbo, to the profiles below on any platform would also help. Links are to Facebook.

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs

Cuban Treat of the Week

Another twofer this week.

Looking forward to talking about my memoir at Books and Books in Coral Gables, Florida and, especially, to meeting the amazing journalist and author, Mirta Ojito. Please share with your Miami-area friends if you can. 6-7 pm.

Register for the free event here.

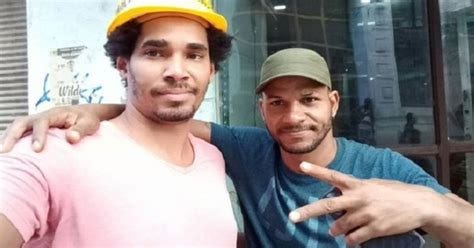

“Patria y Vida” always moves me deeply. I hope you feel the same way after watching and listening. That’s Maykel on the left below.