Anguished mothers blame childrens' deaths on Cuba's collapsed healthcare system

" . . . and it's not the embargo," one mother said of the lack of medicine, negligent care.

Hola y welcome.

Thanks for being here.

I’m focusing on just one scoop this week to give voice to two Cuban mothers who are begging for their stories to be told.

Each woman lost a son in recent days. They blame Cuba’s failing public health system—which includes sending Cuban doctors on medical missions abroad while citizens denounce doctor shortages and abysmal care at home. After too many similar reports over the years, I have to agree.

This has been a tough piece to write, and I think it may be tough to read. Please have a listen to the Cuban Treat of the Week at the end of the post. I promise the music will lift your soul and make you smile.

In the days ahead, I’ll be focusing on our family gatherings, book-related work, and the 25-pound lechón I’ll be roasting on Noche Buena. I look forward to being back on the CubaCurious beat on Thursday, January 3, 2025.

In the meantime, I’m sending you warm wishes for a beautiful holiday full of love, kindness, and peace.

Ana

Uno . . . y solo uno

14ymedio reported this week a shortage of another vital resource at some Cuban hospitals: writing paper and forms. Citizens are complaining that doctors aren’t able to write out scripts, reports, or diagnostic notes. Patients are told to return for the documentation. When they do, often after spending too much money and time traveling in the midst of a severe energy crisis, they’re told the paper still hasn’t arrived.

But it’s the stories of two anguished mothers that caught Cubans’ attention and hearts this week. The two women blamed the collapse of the nation’s health system for the recent deaths of their children, five-year-old Kevin Alejandro Cutiño León, of Bayamo, and twenty seven-year-old Deinier García Escalante, of Havana.

Dayanis León, Cutiño León’s mother, said she brought her son to the hospital seven times but he was sent home each time without treatment. When he grew much worse and was finally hospitalized, he was placed in a regular ward and, again, wasn’t treated. Doctors said the boy’s symptoms were typical for pneumonia. When he vomited blood, they told the mother it was something he’d eaten.

By the time hospital staff took the case seriously, it was too late. After the boy’s death, his mother attempted to file a complaint at the local police station, but officials refused to accept her complaint, saying nothing could be done until proof of a crime was presented.

“I need justice for my baby. They killed him by depriving him of proper medical attention,” León wrote in a Facebook group post. Hundreds of commenters sympathized, many of them sharing their own misfortunes at hospitals and clinics where treatment bears no resemblance to what is offered to Cuba’s political and military elites—as well as foreign “medical” tourists.

Helen Escalante, García Escalante’s mother said there was no ambulance available to take her son to the hospital. Her family had to bring him to a nearby polyclinic “in their arms.” At the clinic, they discovered his glucose was extremely low, but “there was no dextrose to give him, no oxygen, which were the minimum treatments for his condition.”

Escalante shared her devastating news with independent reporter Alberto Arego. “He died in my arms, he fought for air, but he couldn’t find it.” She asked the reporter to spread the word. “Alberto, this is so you’ll keep reporting to people the horrible things that keep happening in Cuba due to a lack of attention to patients and it’s not because of the embargo.”

Meanwhile this week, Cuba’s Health and Sports Commission, after a countrywide survey of medical facilities that lasted several months, reported to parliament that the public health system was in a state of “serious deterioration.”

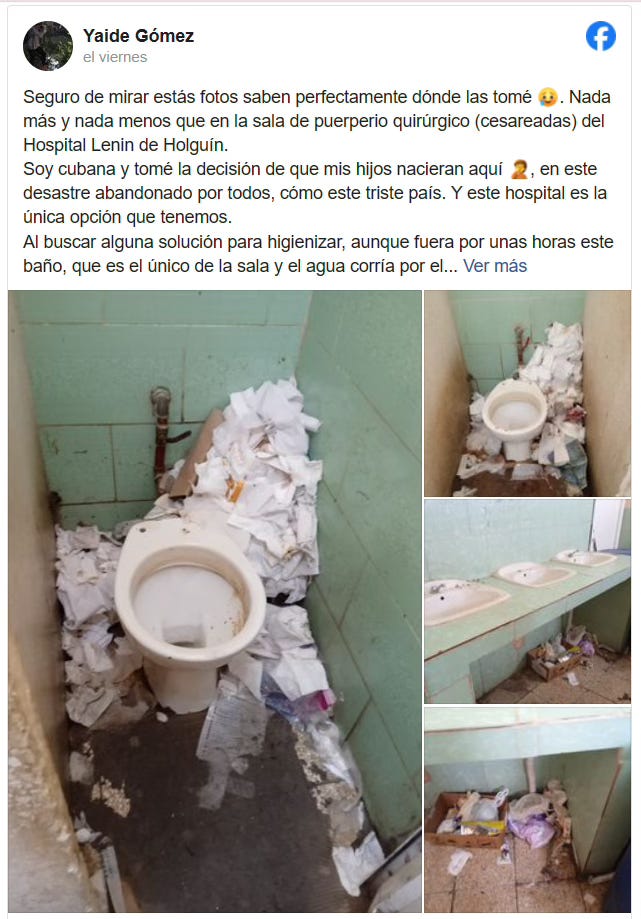

That’s old news for angry, grieving Cubans who—for years—have been denouncing a system they say is dysfunctional, corrupt, and favors political and military elites. Patients say hospital stays require bringing everything from drinking water to bed sheets, their own food, bribes for overworked and sometimes unqualified doctors, and often their own medicine and supplies—from catheters to disinfectants.

These accounts have been common for many years but have worsened with the country’s severe economic and energy crises, and mass migration, which has created shortages of staff at all levels of the public health system. Independent media reports regularly that medical staff across the island are overworked, underpaid, and are at the breaking point.

The regime blames the partial US embargo (food, medicine, and humanitarian aid are exempted). Yet Cuba imported—as an example— $48,000 of penicillin G amidasa, an essential product necessary in the manufacture of the antibiotic from, in October, according to the US-Cuba Trade and Economic Council. The same month, Cuba imported roughly $40,000 in additional, unspecified health care products from US sources.

Cuba’s imports of medicine and medical products from US vendors have varied in volume over the years. But as recently as 2023, the US State Department reported that Washington had authorized roughly $8 billion in medical product sales or donations for export to Cuba. Officials in Cuba called the State Department’s assertions “false and malicious.”

As I read articles showing the volume and variety of Cuba’s imports from the US, I kept hearing Helen Escalante’s words about “the horrible things that keep happening in Cuba” and how “it’s not because of the embargo.” Escalante doesn’t want her pain swept away by believers of the regime’s lies—like Cuba’s prowess in the medical field, free high-quality universal healthcare, or that the embargo is to blame for all of Cuba’s woes.

She’s right. Too many people outside of Cuba believe the regime’s propaganda—and perpetuate it by sharing their limited view of Cuba when they return home.

In November, eleven Massachusetts state representatives—and Massachusetts congressman James McGovern—traveled to Cuba to “. . . learn more about the Cuban healthcare system, climate resiliency strategies and life science innovations,” and “how to get much-needed humanitarian aid to the Cuban people.”

Some of the delegates said they’d been on previous, similar trips to Cuba. At least some of them used campaign funds, legal in Massachusetts for educational travel.

The reps planned to meet “public officials, hospital staff and members of academic and research institutes.” Did the reps meet with or read about mothers like Helen or Dayanis, whose voices are already being silenced or dismissed?

Did the reps know that Cuban disaster victims frequently complain that the government sells them donated goods from other countries—often marked “donation and not for sale”? Just this month, a state-run newspaper touted the government’s sale of mattresses that had been donated for Hurricane Oscar’s victims. The lowest price for a donated mattress was roughly one third the minimum salary in Cuba.

Those are the Cuban people I hope travelers listen to—the Helens, the Dayanises. Not Cuba’s military and political elites, party loyalists, or the coerced staff at hospitals and research centers who are rewarded for sticking to the party line—especially in front of foreign dignitaries.

Cuban Treat of the Week

Please listen. I promise it will soothe your soul and make you smile. Sorry about the ad, just skip it.

Thanks so much for reading! Please share with friends and invite them to subscribe!