Hola and welcome.

Here are your 3 scoops from the Cuban underground, translated from Spanish-language sources.

Número Uno — 11J political prisoner serving 10-year sentence commits suicide

Número Dos — What’s a 2-time Grammy winner doing in a Cuban maximum-security prison?

Número Tres — Of cows and (Cuban) men

This week’s stories reveal a judicial system that is subordinate to the CNA (Cuban National Assembly), which is controlled by the Communist Party—the only political party allowed in Cuba since the 1959 revolution. It is a system of brutal retaliation, designed to intimidate and terrorize—a system where “innocent until proven guilty” turns into “guilty until proven ideologically pure.”

The military and political elites who run the country use the courts to silence dissent and punish citizens who challenge the socialist order. Police can arrest and detain citizens without arrest warrants; they can enter homes and search them at will. Often the accused do not know the charges against them and are denied legal counsel or presented with an uninformed attorney (all lawyers are state employees, private practice is illegal) just before the trial.

The regime trumpeted its 2023 penal code as “inclusive” and “modern,” yet the new code increases prison sentences for crimes like “resistance” and “insulting national symbols.”

Human Rights Watch, like many other human and civil rights groups, criticized the 2023 code as a “legal avenue for repression and censorship . . .” and a way for the regime “to undercut the little civic space that exists in the island.”

For the victims of totalitarianism, due process and the independent judicial systems of free countries—as flawed as they can be—are a dream, a wish, a prayer.

Wishing you freedom, peace—and a little fun—this Labor Day Weekend and always.

Ana

Número Uno

11J Political Prisoner Serving 10-year Sentence Takes His Life

Most of the more than 1000 documented Cuban political prisoners are unknown to the general public, in and outside of Cuba. Yosandri Mulet Almarales was one of those prisoners, a man who did nothing more than protest against the regime in his own Havana barrio on 11 and 12 July 2021.

Mulet, who was sentenced to 10 years for sedition, died Monday at Julio Trigo Hospital, where he’d been taken on 22 August after he’d jumped from the Calabazar Bridge near Havana.

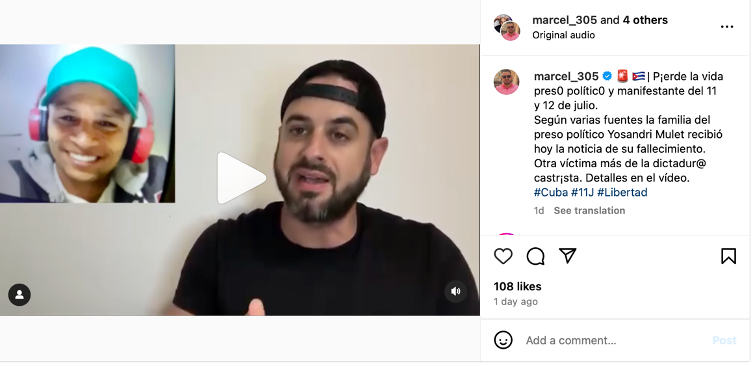

Pro-democracy activist Marcel Valdés reported on social media that details surrounding Mulet’s death were difficult to obtain, because police agents had “militarized” the hospital.”

Mulet’s aunt, Idalmis Salazar González told Martí Noticias that he’d been on a temporary home visit from a forced labor camp. “He was walking with his uncle . . .heading back to the labor camp, because he was due back last Friday. His uncle stopped to talk with a friend and he [Mulet] kept walking. . . . Later, he heard a young man had jumped from the bridge, and it was him,” she said.

“He didn’t want to be imprisoned,” she said. “He was very agitated, he left [at home] the snack and other things he was supposed to take with him.”

Cuban prisoners rely on a biweekly “sack” of basic supplies (food, soap, clean clothes) that families in good-standing (i.e., they haven’t publicly criticized the regime or prison conditions) are allowed to deliver to guards.

Mulet was convicted for protesting on 12 July 2021 in the poor Havana barrio of La Güinera, where police shot and killed protestor Diubis Laurencio Tejeda in the back.

The prosecution accused Mulet of “obeying the exhortations on social media that incited the Cuban people to protest, violently and simultaneously, in different locations and to ignore the authorities, with the purpose of changing the socialist order.”

Mulet had attempted to hang himself, in 2022, while awaiting trial in a maximum security prison, but fellow prisoners found him and saved his life. His attorney tried to obtain a home arrest license, given Mulet’s fragile mental health, but was denied. He did, however, win a transfer to the Toledo forced labor camp, near Mulet’s home.

The regime has historically denied international human rights monitors access to its prisons. Based on well-documented eyewitness testimonies, groups like Human Rights Watch have described Cuban prison conditions as “horrendous”.

Former prisoners report routinely being given rotten food and foul water, the denial of basic medical attention and prescriptions, mental and physical torture, and other violations of the UN’s Nelson Mandela Rules, which represent the minimum basic requirements for upholding prisoner safety, security, and human dignity.

Número Dos

Two-time Grammy award winner turns 41 in Cuban maximum-security Prison

Cuban well-known musician, activist, and Amnesty International (AI) prisoner of conscience Maykel Castillo Pérez turned 41 last week behind bars in Cuba’s Kilo 5 y Medio in Pinar del Rio, Cuba.

Castillo Pérez is serving a nine-year sentence for “insulting national symbols” and “defamation of the revolution’s heroes and martyrs,” among other political crimes.

Castillo Pérez, who goes by his stage name, El Osorbo, is one of the most influential members of the Cuban artist-activist group the San Isidro Movement. Like other members of SIM, Osorbo is committed to non-violence and the defense of human rights and artistic freedom.

Osorbo has faced constant harassment and arbitrary detentions since 2018, when he and SIM began protesting new decrees limiting artistic expression—among the first signed by the “president” Miguel Díaz Canel. Osorbo has been beaten on multiple occasions while “free” by thugs believed to have been paid by the regime. On more than one occasion, neighbors of the San Isidro barrio, where SIM has its gallery headquarters, have defended him from police or offered him aid.

The rapper is the co-creator of the anti-regime anthem and international hit, Patria y Vida, Homeland and Life, which won the 2022 Latin Grammy Song of the Year and Best Urban Song. The song’s title is an inversion of the revolution’s signature slogan, patria o muerte, Homeland or Death, and is prohibited in Cuba.

Osorbo and fellow San Isidro member Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara are among the best known Cuban political prisoners and have consistently received the support of Amnesty International, the UN, PEN America, and at least 15 other human, civil, and artistic rights groups.

Osorbo was detained in the spring 2021 during a street performance. Otero Alcántara was detained later that summer, as he attempted to join the 11J protests. Representatives of the European Parliament and international rights groups traveled to Cuba to attend the artists’ trials but were barred from the courthouse.

The men’s sentences were announced suddenly on June 24, 2022, just as news broke that the US Supreme Court had overturned Roe v. Wade. The court’s timing reflected the regime’s long-standing practice of making controversial announcements or initiating crackdowns during international incidents.

Rights groups have collected numerous reports of both men’s physical and mental torture while in prison, including long periods in solitary confinement, the denial of medical attention, and beatings by other prisoners who are rewarded by the guards for the violence. Amnesty International has issued urgent action alerts on several occasions for both men.

“These convictions are a sign of the cruelty that President Díaz-Canel’s government is willing to inflict on anyone who criticizes the Cuban authorities. The authorities must stop using the criminal justice system to repress the population and take the necessary measures to guarantee the independence of the judiciary and the Attorney General’s Office.” Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International said in a statement.

For more on Osorbo, Otero Alcántara, and their courageous fight for freedom, here’s a recent 3-minute video tribute (English subtitles).

Numero Tres

Of Cows and (Cuban) Men

Cuban state-controlled media has been boasting about “exemplary” court cases, most recently in Songo-La Maya, in the eastern most Santiago de Cuba. Santiago’s Communist Party newspaper touted the process used against the defendants, whose trials were also covered by Televisión Cubana.

One of the cases involved two men who had stolen a cow, butchered it in the field, and then sold the beef on the black market. Authorities are using the case to send a warning to anyone planning this fairly common crime.

Sources have told 14ymedio that the scheme often involves the farmer. The “thief brings a sack full of money to the farmer,” who agrees to the “theft of his cow.” The “thieves” then sell the beef on the black market at much higher prices than what the state would have paid the farmer.

It’s a win-win for the farmer and the sort-of-thieves, but a loss for Acopio, the state agency that purchases and distributes agricultural products and monitors the inventory of livestock to prevent private sales.

“When we have exemplary trials we make sure that the message we are trying to transmit reaches specific audiences,” Geovanis Mestre, one of the judges involved in the cases, said in a Sierra Maestra interview. It’s crucial, he said, that delinquents understand that authorities are scrutinizing beef production and punishment will be severe.”

Exemplary trials have been used since the massive arrests following the 1959 revolution—which many times resulted in death penalties—and have been forcefully criticized by international rights organizations and Cuban activists like Dagoberto Valdés.

Mestre also invoked Article 29, Section 1 of the penal code, which allows the court to require the public’s attendance at exemplary trials. Mestre stressed that the cases are brought “in the name of the Cuban people,” which allows authorities to force the public’s participation.

The sentences have yet to be announced, but exemplary cases tend to carry disproportionately long ones, as happened with 11J protestors.

Yoani Sánchez described exemplary trials as “a dangerous practice” in a recent podcast. “Not only are they very public trials—with zero privacy and full media coverage—used to prosecute common criminals, they’re also used against people who challenge the regime or its socialist order. People who yell a slogan or join a protest can easily end up serving 10 years behind bars.”

It's a practice, she says, that goes beyond applying justice based on the letter of the law, and is meant to “promote fear in the rest of the citizenship.”

“That’s where we are,” Sánchez said. “. . . it’s not just happening, they [the authorities] are boasting and talking about it openly.”